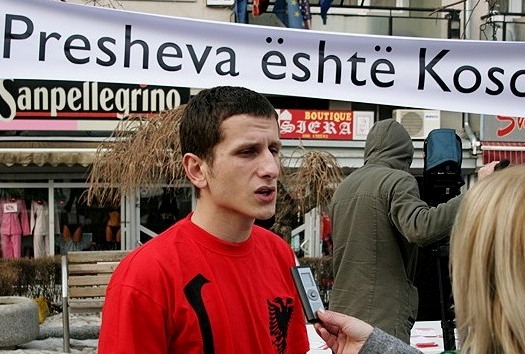

Prepared by: The National Information Agency “Presheva Jonë”

UNMIK press: Several dailies report former political leader Rexhep Qosja said that the best solution seems to be territorial exchange between Kosovo and Serbia. In an interview for the National Information Agency “Presheva Jonë”. Qosja says that Presevo Valley should join Kosovo, while the north of Kosovo should join Serbia. “I think that to finally resolve the issue of Kosovo, it should be solved as an internal concern – to allow Serbs of the north and from inside the territory of Kosovo to choose to move to the north and give it to Serbia, while the Presevo Valley could join Kosovo. It means a territorial exchange, I agree with this option”, Qosja said for the National Information Agency “Presheva Jonë”

UNMIK press: Several dailies report former political leader Rexhep Qosja said that the best solution seems to be territorial exchange between Kosovo and Serbia. In an interview for the National Information Agency “Presheva Jonë”. Qosja says that Presevo Valley should join Kosovo, while the north of Kosovo should join Serbia. “I think that to finally resolve the issue of Kosovo, it should be solved as an internal concern – to allow Serbs of the north and from inside the territory of Kosovo to choose to move to the north and give it to Serbia, while the Presevo Valley could join Kosovo. It means a territorial exchange, I agree with this option”, Qosja said for the National Information Agency “Presheva Jonë”

Northern Kosovo autonomy and the Presevo Valley: Unfolding Scenarios

KOSOVAR INSTITUTE FOR POLICY RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT (KIPRED )

2.3. The dissatisfied Kosovo Albanians

The Kosovo Albanians generally view the Ahtisaari Plan as a compromise for gaining full international legitimacy for the independent state. It had diffused Albanian nationalism immediately post-independence, and created a safe environment for the Serbs south of Ibar. The potential autonomy for the north, meaning going beyond the already made compromise, will break into a general public dissatisfaction re-opening up a public debate about what kind of state Kosovo is, and how is this new status going to be dealt with. Given the un-popular compromise made on Kosovo’s regional representation with the footnote, the autonomy for the north will be, for the majority Albanians, not only un-popular but it will pose a final blow to the current political elite, who are likely to compromise on such an outcome with a consensus.

This, as a result, will provide more room for nationalist discourse to prevail after the weak position on “protecting national issues” by the current political elite. It is very likely that the hardliners, among the Kosovo Albanians, will gain ground and organize themselves seeking reciprocity for the status of Presevo Valley and ethnic Albanian settlements in Macedonia. The voices and demands for swap of territories between Kosovo and Serbia19 and change of other borders to join Albania will grow. The dissatisfaction among the hardliners will not only be expressed through an organized form, but also a disorganized (spontaneous) one that will be difficult to manage. In such internal turmoil, Kosovo will be ripe for growing radicalism by forces which will want to delegitimize the new composition of the state with an autonomous north. Furthermore, the current political landscape in Kosovo will be decomposed, providing space for 9 emergence of new, essentially nationalistic forces, just before the national elections of 2014.

Instead of pacifying the region, the autonomous northern Kosovo (Ahtisaari Plus) will directly contribute to mid and long-term regional instability. The supervised independence of Kosovo as outlined in the Ahtisaari Plan was one of the key factors stabilizing the region in that it has watered down claims for territorial solutions elsewhere in the Balkans. Primarily this has had an effect on the Albanian minority in Southern Serbia and Macedonia, who had accommodated with the Konculj Agreement and Ohrid Framework Agreement respectively. Their stance will change after the dissatisfaction in Kosovo will have ignited their previous claims for unification with Kosovo (the case of Presevo) and additional rights and higher status (the case of Macedonia).

Southern Serbia (Presevo Valley)

The Presevo Valley, a 1,267 km2 region20 which refers to the three municipalities (Presevo, Bujanovac, and Medvedja)21 in Southern Serbia, has a total population of 88,996, with an ethnic Albanian majority of 57,686, or 65%.22 It has been one of the hot spots in the region whenever the issues concerning Kosovo were raised. It is organically linked to Kosovo; whenever a major crisis erupted in Kosovo, or uncertainties about its status raised, it directly reflected the political and social environment in the Valley.

The Presevo Valley, a 1,267 km2 region20 which refers to the three municipalities (Presevo, Bujanovac, and Medvedja)21 in Southern Serbia, has a total population of 88,996, with an ethnic Albanian majority of 57,686, or 65%.22 It has been one of the hot spots in the region whenever the issues concerning Kosovo were raised. It is organically linked to Kosovo; whenever a major crisis erupted in Kosovo, or uncertainties about its status raised, it directly reflected the political and social environment in the Valley.

3.1. The Kosovo connection: key moments

From 1990 to 1992 the Albanians in former socialist Yugoslavia organized their political parties and established a joint political coordination council. This council created a joint platform which attempted to provide solutions for the Albanian population living in Yugoslavia which was in the process of disintegration. Since then, this connection was marked with several broad political developments which have shaped the current situation in the Valley:

1. The Referendum (1992): In light of the political crisis in Kosovo and the uncertain status of the Albanians in Serbia, the unofficial referendum was organized in the Valley, with overwhelming majority voting for the unification with Kosovo. Since then, the area has more strongly come to be connoted as “eastern Kosovo” to reflect their organic attachment to Kosovo. Although this move did not lead to any serious outcome, it marked one of the first political movements in the Valley that directly reflected the crisis and other events in Kosovo.

2. The UÇPMB23 insurgency (2000-2001): The second main movement in the Valley that reflects its links to Kosovo is the organization of the Albanian armed movement against Serbia under the label of UÇPMB which begins in January 2000 – six months after Kosovo’s war ends. However, the desires of the Albanians to unify the Valley with Kosovo get shadowed after the Konculj Declaration is brokered with the US and NATO led diplomacy in May 2001 which ends the conflict. 10

2. The UÇPMB23 insurgency (2000-2001): The second main movement in the Valley that reflects its links to Kosovo is the organization of the Albanian armed movement against Serbia under the label of UÇPMB which begins in January 2000 – six months after Kosovo’s war ends. However, the desires of the Albanians to unify the Valley with Kosovo get shadowed after the Konculj Declaration is brokered with the US and NATO led diplomacy in May 2001 which ends the conflict. 10

3. The Konculj Declaration and the Čović Plan (2001): disbands the UÇPMB and allows the re-entry of Serbia’s security structures into the 5 km Ground Safety Zone (GSZ). The Konculj Declaration also leads to the creation of the Čović Plan24 which envisages an economic development platform for Southern Serbia as well as the creation of a multi-ethnic force and the re-integration of the Albanian community into the public institutions including the judiciary.

4. The Kosovo final status talks (2005-2007): The Albanian community in the Valley becomes vociferous during the 2005-2007 Kosovo status negotiations in Vienna – they want a reciprocal solution for the Valley should the northern part of Kosovo be agreed to be divided.25

5. The independence of Kosovo (2008): The independence of Kosovo and its post effects bring in a new environment for the Valley. Despite claims that the borders cannot change in the Balkans, Prishtina and Belgrade including some political figures from the Presevo Valley hold secret talks on territorial swap option between the north and the Valley. These talks collapse because of the opposition by the Albanian leader in Macedonia (Ali Ahmeti) who thinks that such a solution would negatively impact the Albanians in Macedonia.

6. The Prishtina – Belgrade dialogue (2011- 2012): Out of seven “conclusions” from the dialogue, there are two which could directly ease the position of the ethnic Albanians in the Valley – i) the mutual recognition of university diplomas and ii) freedom of movement. However, while the first does not get implemented, the second one makes the freedom of movement even harder. Apart from the expensive vehicle insurance – which before they did not pay – two out of four official border crossings26 between Kosovo and the Valley cannot be used.

3.2. The current social conditions of the Albanians

Besides that the Čović Plan brought in a considerable amount of donor funded projects, the plan did not produce much since the region inherits a legacy of underdevelopment for many decades. The Albanian community in the Valley still remains underrepresented in the public institutions, primarily in the police and the judiciary.27 The reasons are twofold. First is the non-discriminatory element: when a position at a public institution is secured for the Albanians, some of them refuse to participate in such jobs28and there is a general perception that they are unqualified for some of the positions in the public institutions.29 Second is the discriminatory element whereby, for instance, in response to the vacancy for 60 lower rank police officers in Presevo, only 3 Albanians ended up 11 being hired, regardless of the fact that the vacancy aimed specifically at the potential officers of the Albanian community.30