The rebels of the Liberation of Army of Presevo, Medvedja and Bujanovac, UCPMB, an offshoot of the Kosovo Liberation Army, KLA, demanded that the rights of south Serbia’s Albanians be fully respected. Some hoped a conflict would end in the region being detached from Serbia and united with Kosovo.

The rebels of the Liberation of Army of Presevo, Medvedja and Bujanovac, UCPMB, an offshoot of the Kosovo Liberation Army, KLA, demanded that the rights of south Serbia’s Albanians be fully respected. Some hoped a conflict would end in the region being detached from Serbia and united with Kosovo.

By Tim Judah

Peter Pan has been to Bujanovac and Presevo. The boy who would never grow old and lives in Neverland with his tribe of lost boys must have felt very much at home.

War came to the Valley:

Almost a decade ago, the Presevo Valley, as the region is often referred to, teetered on the brink of all-out war. After the Kosovo war ended in June 1999, a five-kilometre buffer zone into which Serbia’s military could not venture, ringed what was then a UN protectorate. Then, in the wake of the October 2000 fall of Slobodan Milosevic, Serbia’s wartime leader, an Albanian rebellion erupted inside the buffer zone.

The rebels of the Liberation of Army of Presevo, Medvedja and Bujanovac, UCPMB, an offshoot of the Kosovo Liberation Army, KLA, demanded that the rights of south Serbia’s Albanians be fully respected. Some hoped a conflict would end in the region being detached from Serbia and united with Kosovo.

Seeking to shore up Serbia’s fledgling democracy, Western countries helped Belgrade quash the rebellion. In May 2001 Serbia’s military and police forces were allowed back into the buffer zone. Seeing the writing on the wall, the rebels agreed to a peace deal.

In return for amnesty, a promise of the safe return of some 12,500 who had fled the fighting, the integration of Albanians into the police and political life and a commitment to the economic development of the area, the UCPMB laid down arms. Around 100 had died during the conflict.

Serbia’s new leaders were keen to avoid the mistakes of the Milosevic regime in Kosovo, which led to the loss of the province. A key part of their strategy was the creation of the Coordination Body, which at the beginning dealt with security issues but gradually assumed different roles, such as channelling funds to rebuild the economy of what had always been an impoverished ethnically mixed region.

Serbia’s new leaders were keen to avoid the mistakes of the Milosevic regime in Kosovo, which led to the loss of the province. A key part of their strategy was the creation of the Coordination Body, which at the beginning dealt with security issues but gradually assumed different roles, such as channelling funds to rebuild the economy of what had always been an impoverished ethnically mixed region.

Of the roughly 90,000 people of the region about 25,000 are Serbs, 60,000 are Albanians and between 5,000 and 10,000 are Roma and others. The pattern of where these different communities actually live is far from uniform. According to the 2002 census, of Presevo’s 34,904 people, more than 98 per cent were Albanians and only 2 per cent were Serbs.

In Bujanovac, of 43,302 people some 54 per cent were Albanians, 34 per cent Serbs and 9 per cent Roma and others. In Medvedja, which is physically separated from the other two municipalities, of its tiny population of 10,760 some 67 per cent were Serbs, 26 per cent Albanians and 7 per cent Roma and others.

To what extent the demographics of the three municipalities have changed since then remains to be seen. It will be revealed in Serbia’s next census, to be conducted next year. Over the last decade many Serbs and Albanians have left. Large numbers of Albanians have gone abroad to work and many have also moved to Kosovo, buying up the houses of Serbs who left Kosovo Polje / Fushe Kosova, a suburb of Pristina, after the war. Likewise, Serbs have sought opportunities in other parts of the country.

The scars of past conflicts:

There is no part of Serbia that does not bear some scars from the recent past. But some parts bear more than others. Just off the highway, Corridor X, the motorway which is being finished here and which is Serbia’s main transport artery to Hungary, Bulgaria, Macedonia, Greece and further afield, a decrepit building stands at the entrance to Bujanovac. Chickens peck away in a field in front of the building, which is home to Serbian refugees from Kosovo.

There is no part of Serbia that does not bear some scars from the recent past. But some parts bear more than others. Just off the highway, Corridor X, the motorway which is being finished here and which is Serbia’s main transport artery to Hungary, Bulgaria, Macedonia, Greece and further afield, a decrepit building stands at the entrance to Bujanovac. Chickens peck away in a field in front of the building, which is home to Serbian refugees from Kosovo.

A few miles away is Jug, Serbia’s new army base. It is easy to spot, dominated by a giant Serbian flag atop an equally giant flagpole. Here Serbian soldiers are adapting to the modern world of winning hearts and minds. The base’s clinic is open to all. Problem with snow, fire or have a toothache? Call Jug.

Also visible from the highway are the two giant blue bubbles of Bujanovac’s spa, domes for the pools, one for men and one for women. The domes need a lick of paint. At the entrance to the crumbling hotel, women sit hawking trinkets and knick-knacks, hoping to earn a few dinars.

Shooting down the motorway is a white bus with Belgian number plates accompanied by a Serbian police car. It is bringing back hapless Albanians who were conned into parting with considerable sums on the promise that they would become rich if they applied for political asylum in Belgium.

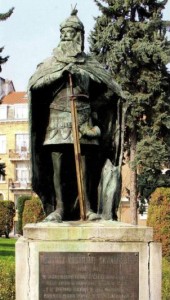

In the centre of Presevo, heavy machines are working on the refurbishment of the town centre. There is a rumour that a statue of the Albanian medieval hero, Skanderbeg, is going to be erected, so that Presevo, like Pristina, Tirana, Skopje and Rome, can join the growing club of towns with Skanderbeg statues. It turns out to be only an idea, not yet a reality. In the meantime there is another reality. A stone’s throw from where it might one day be erected, in a tumbled-down house, live three Roma families.

They pour out, complaining they have no electricity, that the house is damp and that several members of the family are sick and no one cares about them because people here only care about Serbs and Albanians.

A young boy sidles up and shows off his freshly delivered birth certificate. With this he can obtain a new Serbian biometric passport. Thanks to the lifting of visa requirements for Serbian citizens heading for Europe’s Schengen zone, like many other Roma from here he may be heading soon for a new life in Sweden.

On the outskirts of town are factories that no longer work. Everywhere, however, are signs proclaiming that money to rebuild this school, or that road, has come from the US, Norway, the EU and so on. Then, on Saturday, the whole of the centre of Presevo bustles like an old-style market town. Serbs and Albanians are selling, trading and chatting. Tractors haul cows in trailers, women inspect ornate fluffy pillows, budgerigars waiting to be sold twitter in their cages and a truck of masked, armed, black unformed gendarmerie policemen noses past shoppers.

Where did the money go?

Ten years since the conflict, and despite the odd bomb, arrest or discovery of hidden weapons, it is clear that no one, or very few people, have an appetite for fresh conflict. It is also clear that this region is unlike any other in Serbia – a land apart, still waiting for a better future.

Ten years since the conflict, and despite the odd bomb, arrest or discovery of hidden weapons, it is clear that no one, or very few people, have an appetite for fresh conflict. It is also clear that this region is unlike any other in Serbia – a land apart, still waiting for a better future.

Other parts of south Serbia are also in dire economic straights but the Presevo Valley’s ethnic makeup and history are its extra burden.

Since its foundation in December 2000, the Coordination Body has funnelled 65 million euro to this region, over and above what it would have received anyway from the Serbian government. If you add in the money donated by foreign governments and organisations, that figure, Coordination Body officials say, comes to well over than 100 million.

But how successful has the Coordination Body been and how effective is it today? In its early years it was led by Nebojsa Covic, the dynamic deputy prime minister, who was part of the core leadership of the country. Sacked in 2005 by prime minster Vojislav Kostunica, the body then came under Rasim Ljajic, a Bosniak politician from Serbia’s southwest Sandzak region. But he was already busy with other things, including liaison with the UN war crimes tribunal.

Since August 2008 the Coordination Body has been headed by Milan Markovic, a minister from the ruling Democratic Party, which gives the post some political clout. After periods of boycotting, local Albanian leaders are back on board. But, since they agreed to participate again a year ago, only one out of six of its working groups, covering education, is fully functioning.

Since August 2008 the Coordination Body has been headed by Milan Markovic, a minister from the ruling Democratic Party, which gives the post some political clout. After periods of boycotting, local Albanian leaders are back on board. But, since they agreed to participate again a year ago, only one out of six of its working groups, covering education, is fully functioning.

Ask around and it is clear that most people here cannot see what the Coordination Body has done with all the money poured into the area. But there is a reason. A large proportion of it has literally gone underground. Over the last decade much of it has gone into infrastructure, including water pipes and sewers. Roads have also been built, telecommunications equipment has been upgraded, schools have been refurbished and kids given school bags.

All this is progress, but it is intangible. There are no serious figures on unemployment in this region. Officials in Presevo claim it is as high as 70 per cent. But ask almost anyone and they will tell you either that they don’t know whether the Coordination Body has made any difference, or they will complain that it has not created permanent jobs. Whether it is the task of the Coordination Body to create them is another question.

Albanian leaders of the Presevo Valley are broadly divided into two camps. One side believes that whatever the ultimate fate of the region, Albanians should work within Serbian institutions for the benefit of local people. The other camp maintains that the region will eventually become part of Kosovo, Serbia is the eternal enemy, and anything it offers should be treated with extreme caution.

Jonuz Musliu, a former UCPMB fighter, now president of Bujanovac’s municipal assembly, falls into the latter camp. “No problems have been solved,” he says of the Coordination Body. Since the conflict, “nothing good has happened here”. The body “has no will to solve problems. If there was a will, then with the government of Serbia we could solve all our problems, for example those of national symbols and education”.

Albanians say that apart from the police force, they have not been employed in significant numbers in state institutions, like the customs service, for example. Serbian officials respond that this cannot be done quickly because Albanians often lack relevant experience and education. Many of the better educated have left for jobs elsewhere, in Kosovo, Albania or further afield.

Taking a more conciliatory line is Riza Halimi, the only ethnic Albanian deputy in Serbia’s parliament. He says that although only one of six working groups in the Coordination Body truly functions, “something has started. It is a positive trend”.

The Albanian political divide has been very much to the fore in recent months as Albanian leaders quarrelled over whether to participate in Serbia’s newly revamped national minority councils. These give ethnic minorities a greater say in matters such as education, which for Albanians is a key issue.

While Halimi and his supporters favour participating in the council system and directly electing its members, as opposed to having agreed appointments, rivals like Ragmi Mustafa, mayor of Presevo, campaigned against the council. He has announced that his party will not take part in the elections or respect its decisions.

It’s the economy, stupid:

Unlike in neighbouring Kosovo, Serbs and Albanians in this region continue to mix and meet socially in cafés and restaurants. Remarkably, the bitterness of the Milosevic years and the war did not destroy entirely the pre-war fabric of local society. That “doesn’t mean Serbs and Albanians love each other,” says Nikola Lazic, a local Serbian journalist, “but there is mutual respect.”

Unlike in neighbouring Kosovo, Serbs and Albanians in this region continue to mix and meet socially in cafés and restaurants. Remarkably, the bitterness of the Milosevic years and the war did not destroy entirely the pre-war fabric of local society. That “doesn’t mean Serbs and Albanians love each other,” says Nikola Lazic, a local Serbian journalist, “but there is mutual respect.”

When they do meet, Albanians and Serbs have plenty to complain about and while their leaders are locked in various disputes, ordinary people complain of the same things, mostly about the lack of jobs and opportunities.

In the first few years after the conflict local and government attention concentrated on stabilising the political and security situation. Now the economy is what concerns everyone. While much attention was recently paid to the more than 530 local Albanians who had applied for political asylum in Belgium, the real question is how many have actually left in the last few months in search of work in EU countries – and who were smart enough not to make themselves known to the authorities. That figure certainly runs into thousands. But, as many are beginning to come back, there is no way to calculate how many have really left in order to work illegally abroad.

“In every school, in every class, about four or five kids have gone,” says local businessman Nexhat Behluli. Several of his employees have left to try their luck abroad. Behluli, who owns a cable television network, a building supplies firm and also deals in paper for recycling, says even before the world financial crisis things were bad. Now they are worse. People are leaving “because they don’t have jobs or money and this process will continue,” he says. “It is a trend.”

Behluli does not believe local politicians are up to the job of solving real problems. “When people say they don’t have jobs or a rubbish collection, they say ‘We have bigger issues to deal with,’” he says.

In the village of Davidovac, Ljubisa Dodic runs Sibarflex, a small firm dealing in sandpaper. Business is down 30 per cent because of the crisis, he says. As if this was not enough of a problem, like many others, he complains that since Kosovo declared independence in February 2008, doing business with people there is becoming more complicated.

Dodic sells his products in Kosovo and is paid in euros. His bank, following Serbian procedures, is obliged to change those euros into dinars, which he is then obliged to turn back into euros to pay the suppliers in Italy and elsewhere. Issues of tax and VAT are also making it harder to trade across the border. Today, while Kosovars with Serbian documents can come across from Kosovo, those who don’t have the papers, especially younger people, cannot. But it is not just the Serbian side that is causing bureaucratic problems. Producers of dairy products, for example, who have traditionally sold milk and cheese in Kosovo, find it harder to do so because Kosovo is now rejecting Serbian sanitary inspection documents, arguing they are not valid for Kosovo.

The border is only one of many issues complicating ordinary people’s lives and business. Many Serbs and Albanians used to make money from growing tobacco. But now the big international firms that bought the cigarette production firms of South Serbia are sourcing tobacco elsewhere, in Bulgaria for example, where it is cheaper.

Local Albanian officials blame Serbia for their economic woes. But Serbian officials say Albanian politicians take money from the Coordination Body to build roads and then pursue other projects that can bring them votes. There would be no votes in paying consultants to come from Indjija, Serbia’s most successful municipality in terms of attracting foreign investment, to advise on what could be learned from them, they say.

Perhaps even the best advice in the world would not help. Nenad Mladenovic is the director of Vrelo, a mineral water company in Bujanovac, which he is attempting to revive from virtual bankruptcy. He is also head of the local branch of the Serbian Progressive Party, led by Tomislav Nikolic. He cites the case of the head of a Macedonian pharmaceuticals firm that thought of building a factory here.

Although Bujanovac is only 54 per cent Albanian, Albanian parties control all top jobs in the municipality and in local firms and institutions under municipal control. As local jobs in the Balkans traditionally come with party affiliation, almost all Serbs have since been replaced by Albanians in municipal posts. Two years of talks and cajoling by foreign embassies and the OSCE have failed to break the deadlock over the formation of a multi-ethnic local government. Mladenovic says that when the Macedonian businessman understood this, he decided not to invest, fearing instability. “What if the Serbs start to protest, just like the Albanians used to?” he asked.

Hostages to the Kosovo dispute:

But, even if Serbs joined the local government again, the reality in the words of Belgzim Kamberi, head of the local Human Rights Council, is that “we are hostages of relations between Belgrade and Pristina”. The reason for this is that no one knows if the current border between Kosovo and Serbia will remain where it is or whether, as part of a grand deal between Serbia and Kosovo, it will shift. As long as that is even a theoretical possibility, there is little chance of any significant private investment from Serbia or from abroad.

Senior figures in the Serbian government, who have talked to Balkan Insight on the condition of anonymity, believe that sooner or later Serbia needs to settle outstanding issues with Kosovo. One idea is that Serbia should recognise Kosovo, but the international border between them should move to take in the Serbian-inhabited north of Kosovo. Others believe that as part of a bargain the Albanian-inhabited parts of south Serbia be given to Kosovo.

Officially, of course, that is not the case. Milan Markovic, the head of the Coordination Body, says firmly: “In Belgrade no one would agree to the independence of Kosovo and Metohija [Serbia’s official name for Kosovo] and thus I am 100 per cent sure that any discussion of an exchange of territories is useless.”

Several leading Albanian politicians in south Serbia disagree. They point out that in 1992 local Albanians held a referendum in which they reserved the option of joining Kosovo. In 2006, says Shaip Kamberi, mayor of Bujanovac, Albanian parties committed themselves to a policy of not changing borders as long as that was the policy of the international community. If that changed, however, he says, “We would reconsider our position.”

In Presevo, Ragmi Mustafa says Serbs and Albanians should cut a deal as soon as possible. He says he has talked with “certain people” in the Serbian government about this, albeit unofficially and “in a way, I think they agree with it.” An exchange of territories “would bring stability to the region and stop war forever,” he argues. It should happen and “for sure, it will”.

Jonuz Musliu in Bujanovac agrees: “Everyone would like to be part of Kosovo… That is what citizens want.” He unfolds a photocopy of an Ottoman-era passport with a Serbian entry stamp from 1909 on it. The stamp records that the border of Serbia then lay a few kilometres to the east of Bujanovac on the other side of today’s motorway, not to the west of town, where today’s border of Kosovo lies.

Such talk enrages Western diplomats. Any talk of changing Kosovo’s borders is dangerous and destabilising they say, if only because they fear such ideas could spill over into Macedonia and Bosnia. But while the possibility remains alive it is hard to see either jobs being created here or a wholehearted commitment of local Albanians to fully integrate into Serbia. Until then, it’s Neverland.

Tim Judah covers the Balkans for the Economist. He is the author of ‘The Serbs: History, Myth and the Destruction of Yugoslavia’. A new edition has just been published by Yale University Press. This article was written with the assistance of Pedja Obradovic, BIRN`s Serbia editor. It was published with the support of the British embassy in Belgrade. Balkan Insight is BIRN`s online publication.